Top Ten Most Influential Games

As a writing exercise, I've chosen the ten books, albums, movies, and games that were most important in defining me as a person, and challenged myself to explain why.

Some of these set my artistic tone or left huge imprints on my personality, others changed the course of my life or career. With each item I can say, "if not for this, I would be someone else right now." But why? It's a surprisingly hard question to answer. A strong feeling would compel me to put something on the list, and then I'd realize I had no clue how to unpack that feeling.

The Top Ten

(Unlike the other lists that are in chronological order, this one goes by level of influence, from least to most.)

These two games are one continuous 3D fantasy land, full of dark corners and exotic critters. They fulfill the promise that the game Ultima IX made years earlier, but without the bugs and performance issues. It's an open environment: You can just wander around and explore, ignoring the built-in plot and behaving unpredictably, and any direction you go will be an adventure.

These are the only games I've really taken to as an adult (a line I draw somewhere around the age of 25). Sure I've been addicted to others for a while, but it's Oblivion and Skyrim that I keep coming back to, just to poke around. I've even written little stories, and made comics using screenshots from the game. So why do I keep coming back? I think I have an answer for that. I call it the "Alice In Wonderland" effect.

In the original story by Lewis Carroll, Alice falls down a rabbit hole into a twisted realm filled with creatures that are all different shapes and sizes, but have one thing in common: They are all mentally deranged. From the Cheshire Cat to the Mad Hatter, some characters are helpful and some are violent, some can deliver speeches and some can only caper and drool, but the only character who even comes close to sanity, or even aspires to it, is Alice. Even the landscape she wanders through is deranged.

... And that's what it's like to play a single-player computer game - including all the games on this list. That's what it's always been like. Everyone around you is a simulation, following a limited script, and the more complex the simulation, the more likely the script is going to run off the rails and make the character behave in some hilarious or upsetting way.

In Oblivion for example, a guard at the town gates might greet you warmly as you approach, and continue to stand there impassively when you slaughter the guard right next to him. A shopkeeper might ask you to fetch a rare ingredient from far away, then happily reward you for the pile you've just lifted straight out from her own display case, right in front of her. A king might stand up and declare you the hero of the realm, then turn sideways and walk headlong into a closed door - and keep walking at it for as long as you're in the castle. These are supposed to be real people, and if you try to accept them as real, you also have to accept that they are seriously weird.

You are down the rabbit hole, wandering alone amongst the insane. Or, if you believe the framing device of the original Lewis Carroll story, you are dreaming: Wandering alone inside the labyrinth of your own mind, confronting all the deranged fragments of your own personality. Sounds like a great way to spend your leisure time, right? To an introvert, it's actually a bit refreshing.

Here's a bunch more writing I've done about these two games, including some comics:

Oblivion:

Skyrim and Comedy Wolf:

9. (Age 17) Doom

It's hard to believe that this game is so far in the past. It's hard to believe that the gameplay experience it delivered - so novel and exciting at the time - is now quaint and boring for a generation of gamers used to playing Minecraft and Halo on iPads.

I remember the first few minutes I saw this game in action at a friend's house, in his dank suburban living room. I was astounded. A real first-person view, running full screen! And you could play head-to-head! I was instantly determined to break away from the Apple IIgs and assemble a PC-compatible computer. I was just missing too much in the gaming world. I had already seen Might And Magic 4 and Star Control 2, and this was the last straw.

With help from my parents, I went out and bought a motherboard, a 486-DX2 CPU, a couple of disk drives, a 500 megabyte hard drive, and a whopping 16 megabytes of RAM. Then I put it all inside a full-size computer case, made of thick steel. It was nearly three feet tall, weighed over 25 pounds, and was colored a hideous industrial brown. It looked like a giant brick of tofu. I called it "LOAF", and carved that name into the plastic on the front with a soldering iron, including the quotation marks. The display - a 19-inch "NEC Multisync" - weighed another 50 pounds and cost almost as much as the rest of the computer combined. That's a total of 75 pounds. (For contrast I am currently typing this on a portable computer with a ten hour battery life that weighs about 2 pounds.)

My friend Brent visited one day and brought his own computer - a similar beast - and we spent hours upon hours messing with thick serial cables and configuration files in MS-DOS, finally meeting with success late in the day, and then we went head-to-head playing Doom for most of the night. It was a blast, and worth the trouble. Soon we got modems and started tying up the phone lines for hours at a time playing remotely. My sisters liked me even less for that.

My friends and I began a tradition of dialing each other up at night, jumping into some Doom level together, and then blasting through it in co-op mode while we sent chat messages back and forth. We talked about school, philosophy, movies, our crappy summer jobs, and our meager romantic lives. It became one of our favorite ways to have meaningful conversations, and it folded in with the rest of our habits. Eventually it felt normal to start up some deep conversation any time we sat down at a game console together. Looking back, I'm grateful that my friends were as emotionally candid and non-judgmental as they were. I don't think it was typical for teenage boys.

What was typical, is the way we all laughed when things went "BOOM". (The game made it into my "top ten list of accidental funny moments in gaming" twice.) Brent and I moved on to Duke Nukem and Shadow Warrior, but my memories of Doom remain the most vivid.

8. (Age 22) Starcraft

Picture this. You're standing in a messy bedroom, on the second floor of a beat-up victorian house. The carpet is brown and hairy and covered with the materials of a third-year college student - binders, textbooks, laundry, food wrappers. There are also cables looped around, mostly for the stereo, but one cable stands out from the others. It's thick and rubbery and colored an intense industrial blue. It snakes down from the huge boxy computer on the desk, across the carpet, and out into the hallway, where it connects up with five other fat blue cables at a small plastic box, dotted with furiously blinking lights.

It's called a CAT-5 network cable, and it puts the whole scene in a specific historical context, more so than the clothing, the posters on the walls, the stereo, or anything else. This is the year 1996.

As I stood in that room, I was watching a UC Davis student play a computer game. He built little armies of knights and sent them sprinting across a map, where they clashed with the armies of seven other players, representing seven other students on seven other computers elsewhere in the house. It was my first good look at a modern real-time strategy game where more than two people could play. The only networked games I'd seen before this were first-person-shooters.

The game was Warcraft II. I was hooked, and the second a chair opened up, I elbowed my way in and started clashing armies on the map. We all played long into the night, until it was time to drive home, and shortly after that I helped wire up my own house, and clashed armies with my three housemates. The game was fun, but what was even more fun was hearing the smack-talk and the shouts of triumph or agony from down the hall, as players got surprised or double-crossed or made terrific comebacks or forehead-slapping mistakes. Observers could even sneak from room to room and drop hints, or just cackle madly at some battle that only they could see coming. It was a cross between a sporting event and an old-fashioned "LAN party" like the ones I'd attended back in Santa Cruz.

We had fun playing the game, but we were also busy, and it was hard getting everyone together. It was also hard to find enough networked computers in one place, outside of the official college dorms, which were expensive and had anti-gaming policies. The computer labs were locked down and monitored, of course. WIFI was rare and hideously expensive.

Fast-forward three years and I'm at UCSC. Starcraft has been out for a while and it's a huge success; practically a cultural phenomenon. I have a big fuzzy friend group of mostly nerds and we all love to play it, but playing it in different buildings is just not much fun since we can't talk smack and hear each others' cries of anger. Internet-fueled piracy to the rescue!

Using a collection of software gathered from the dark and spooky corners of the internet, I built a custom Starcraft installer, with all our favorite sound effects (mostly fart noises, or our own voices dubbed over the units) and extras built in, and burned it to a dozen CDs and handed them out. Every couple of weeks, somewhere between five and ten of us would storm into an empty computer lab like a crew of viking invaders, carrying snacks and drinks, and insert the CDs into a row of computers. The CDs ran an auto-launch script that killed the password protection on the screen saver, then installed our customized game, and away we went.

Our weekly games didn't change my philosophy or my personality, but they strengthened a lot of relationships, prompted fun conversations, and created lots of memories that still come up today, almost 20 years later. Now my nephews are hooked on sequels to the same strategy games, and these ancient lab gatherings have developed a mythical glow. They have become "the good old days", when the amusing smack-talk and sportsmanship was more important than expertise or bragging rights. Now every time I play a head-to-head game - from Call Of Duty to Puzzle Fighter - I spend as much time cracking jokes as I do strategizing. It's just the way you're meant to do it.

Back in the early home-computing days, there was actually a genre of games that didn't have any animation, or art, or music. The only interaction you did was typing words on the keyboard, and getting words back from the computer in response. It was interactive fiction at its most basic, where you played an active role in the story, but the story unfolded primarily in your imagination, as though you were reading a novel.

Planetfall was the first game of this style that I played. Like most of my software collection from the 1980's, I have no idea where I got it from. Perhaps I pirated it from a friend of school; perhaps I downloaded it as a disk image from some dial-up bulletin board. I can almost visualize the disk, a 5.25-inch square with a paper sticker on it, labeled "PLANETFALL" in sloppy block letters with a felt-tip pen. What I definitely remember, even 30 years later, are the scenes I imagined while playing the game.

To get a summary of the plot you can read about it on Wikipedia, but the plot doesn't really matter, because it's not why the game was influential to me. The lasting impact of Planetfall was to inspire me and my friends to recreate the text-based interactive fiction format that it used, using live humans instead of a computer. We called it a "Human Adventure Game" (kind of a stupid name in retrospect) and it went something like this:

Zach: "You are standing in room with a large bay window to the north, showing a sparkling lake in the distance. Most of the floor is taken up by an enormous persian rug. There is a desk on the western wall, and a door to the south, currently closed."

Me: "Look on desk."

Zach: "You see a few crumpled scraps of paper resting next to a typewriter. A bottle of 1920 LaGrange Firewater is next to the typewriter, with a cork jammed in it."

Me: "Throw bottle out window."

Zach: "With a hideous crash, the bottle explodes against the bay window and the fragments rain to the carpet. The bay window is made of thick plate glass however and is unharmed, except for a huge splotch of Firewater dribbling down the inside, reeking like car exhaust. You hear a surprised shout from the south."

Me: "Open door"

Zach: "The door opens easily. To the south you see..."

And so on. You get the idea.

Since playing a game took the form of a dialogue, we could play any time or place. We would often strike up a game while walking in the woods, or sitting in a restaurant gulping endless refills of soda. Other times we would play on computers, connected over the modem, or hot-seat style on a single computer, socializing or tinkering with electronics between turns. I managed to preserve some of those games and put them online.

It was an interesting cross between co-writing a story, where everyone shared in the creative process equally, and directing a play, where one person could impose their vision and the others worked within it. The idea is simple but we took it in a number of surreal directions. For example, we would often add each other as characters into the game:

Zach: "To the south you see Alex, blocking the doorway and looking alarmed. He is wearing an apron and holding a spatula. The smell of pancakes drifts into the room. Alex says, 'what the hell was that?'"

Me: "Tell Alex, 'I was just testing the window.'"

Zach: "Alex looks over your shoulder and sees the huge stain on the window. 'Well the next thing you can test is a mop and some water. And pick up all that glass.' He walks back over to a stovetop and flips a pancake in a frying pan."

Sometimes we would add ourselves into the game, and then make blithe commentary about how the game was going. In this game with Alex, I appear as myself, operating a refreshment stand. I also throw in our graphic arts teacher from high school, and for no reason at all I make Alex female without telling him. In this game, Scott has me playing the part of Charles Darwin, commanding an expedition of Warcraft peons to parts unknown. Looking back, it's telling how so many of these games started with a defiant escape of some kind - Darwin jumping out his own window, Alex smashing his way out of his room - fulfilling a desire to escape our own lives and feelings of conformity.

For a while I was naïve enough to think we had created a novel art form, even though we had really just re-invented Dungeons And Dragons - with the concept of a DM and players - under more relaxed rules. Still, it was a great creative outlet for us, and deepened our relationships at the same time it refined our senses of humor. The built-in emphasis on the comedy rule of "yes and" turned us into better collaborators, I think.

Eventually we all got too busy and preoccupied to play. The last recorded game I have is of Alex and I playing over the internet, set in a Harvey Mudd College women's dormitory since I had just gone on a date with a woman who lived there and the visit was fresh in my mind. It co-stars Jodie Foster and ends with a psychic battle. Of course.

I predict that in about ten years - or perhaps less - when VR becomes mainstream enough to really work - there will be a kind of revival (or perhaps re-re-revival) of this idea. Young people will don a pair of sunglasses with earphones, put on some fingerless gloves, and architect their own sets and theaters, with enough interchangeable parts and props to build an adventure on-the-fly for their friends to roam around in, and the concept of the DM will morph into the VM - the Virtual Master. Imagine the fun of it: Even if you're all spread across different cities working your day jobs, you and your friends can get together after work and participate in a murder mystery, locked together in a creepy victorian mansion with a thunderstorm outside, making it up as you go along while the VM whispers direction in your ear and queues up scripted events like the chandelier crashing onto the dinner table or the lights going out.

(Also, William Gibson will get another round of well-deserved applause for predicting this back in the 80's.)

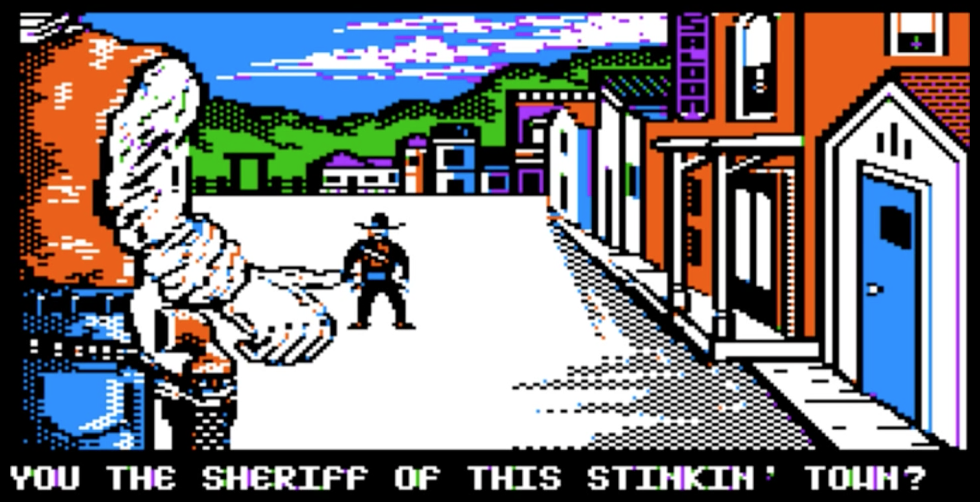

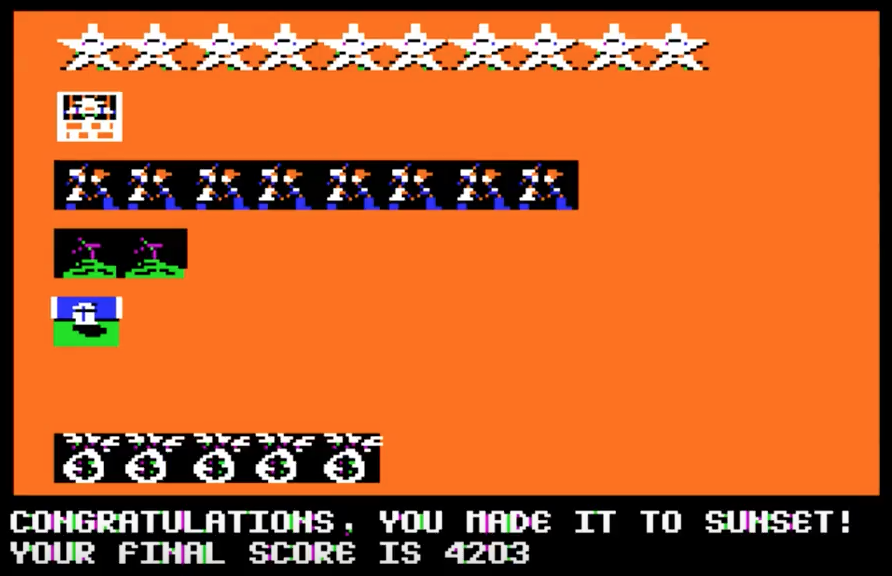

This was by most accounts a dumb little game. Yet it managed to teach me an important idea, one that has guided me in making plenty of life-shaping decisions as an adult.

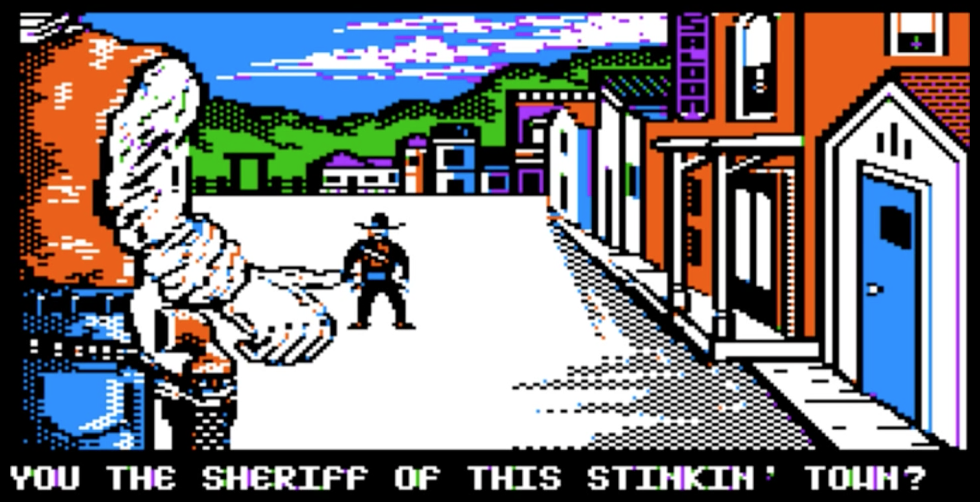

In Law Of The West, I played the new sheriff of a small frontier town, having a series of conversations with various townsfolk. Each citizen walked out into the middle of the screen with a herky-jerky animation, then turned to face me and started talking. I got three or four responses to choose from, and the dialogue branched out. This went on for a while until the citizen walked away, or until they drew a weapon - or I drew mine with the joystick - and somebody got gunned down. Over the course of a game I could have conversations with the town drunk, the local doctor, a tough-talking cowboy, a schoolteacher, a kid, and some others. Depending on how I steered the conversation, I got a chance to stop a robbery, drive a troublemaker out of down, or even go on a date.

In Law Of The West, I played the new sheriff of a small frontier town, having a series of conversations with various townsfolk. Each citizen walked out into the middle of the screen with a herky-jerky animation, then turned to face me and started talking. I got three or four responses to choose from, and the dialogue branched out. This went on for a while until the citizen walked away, or until they drew a weapon - or I drew mine with the joystick - and somebody got gunned down. Over the course of a game I could have conversations with the town drunk, the local doctor, a tough-talking cowboy, a schoolteacher, a kid, and some others. Depending on how I steered the conversation, I got a chance to stop a robbery, drive a troublemaker out of down, or even go on a date.

Since I was a 13-year-old kid, I believed that the way to win was to do a great job as sheriff, and that meant preventing robberies. I hunted through the dialogue tree for each citizen, and discovered that almost all of them - even the schoolteacher - could tell me about a robbery in progress or about to happen, and then there would be an action scene where I drew my gun and shot down the bandit before they escaped. Kapow!! Dance, varmint!

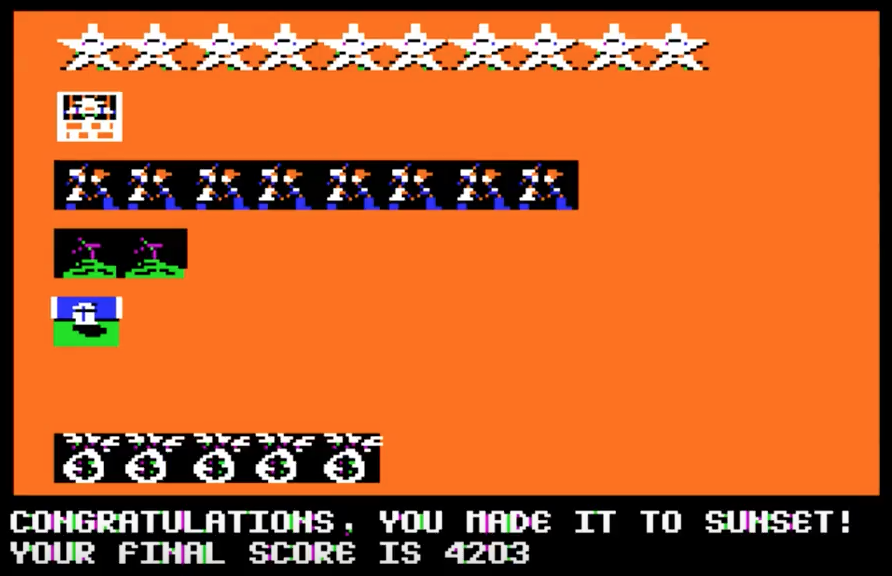

After eleven conversations (or less if I got shot) the game would end and show a summary of my score, with a collection of icons. Each time I played I was able to get more and more "badge" icons, and fewer "flying moneybag" icons, showing that I prevented more robberies. That got me feeling pretty good - but there was a whole section of my score table that remained stubbornly blank. With 11 conversations, the most I could earn was 11 badges, so what was the point of all that extra space?

Eventually I realized that the space was for different types of icons. There was more than just the badge and the money bags. If I arranged a date with the schoolteacher I got a little icon of two people kissing, down on the next row of the table. If I acted tough and arrested a troublemaker, I got an icon of a dude behind bars in another row. If I drew my gun and shot an innocent person, I got a creepy icon of a gravestone on the bottom row. Bad sheriff, no cookie.

This was frustrating to me because I wanted all the icons, all at once, to maximize my score. But there were only 11 conversations, so completing the table was impossible! The best I could do, after learning the game really well, was choose some arbitrary collection of badge icons and heart icons and money bag icons, and aim for that. If I didn't set my own goal, the game would be pointless.

Some time later - months or years later - I remembered this game, and suddenly I realized the lesson it was teaching me:

Every situation I get into is a chance for me to pursue something, and usually the thing I choose to pursue will be the thing I find. If I don't make that choice consciously - if I don't diversify my pursuits and learn to find more than one kind of thing - my world will close in around my pursuits like a thickening forest, and my ability to find happiness will close in at the same time.

Every situation I get into is a chance for me to pursue something, and usually the thing I choose to pursue will be the thing I find. If I don't make that choice consciously - if I don't diversify my pursuits and learn to find more than one kind of thing - my world will close in around my pursuits like a thickening forest, and my ability to find happiness will close in at the same time.

There is value in making money, yes. There is also value in romance, in spending a day at the beach, in making people laugh with a really good joke, in being useful, in reducing waste and resolving conflict, in hearing a great story, in petting a cat, in showing appreciation for a gift. Not for some other end - not for a future plan or an icon on a score table - but because each of these can be satisfying on its own terms. It also becomes cumulative, because if it's easier to find value in the present, it's easier to see a path to the next valuable thing.

This matters, because no matter how you might insist you are going with the flow, or seizing the day to drive your plans forward, being alive forces you to make a thousand decisions on autopilot every day. You simply cannot pay attention to everything; you cannot fully exploit every opportunity, and those automatic decisions will shape your fate as surely as anything else you do. If your habits are bent around pursuing only one or two things, an entire universe will pass around you unnoticed, carrying a universe of opportunity with it. You may eventually find what you seek, but you may not find much else.

Years after internalizing that, I also had to confront the flipside: How much of something is enough? Should ambitions only grow in scale, or should they also recede?

How much money is enough, once you're well fed and safe? Is three money bags enough? If you give up two hearts, in exchange for three more money bags, will you be happier?

How much travel is enough, when you've explored places on the opposite side of the earth, and so many of your ancestors only went a couple hundred miles at most?

How much should you worry about any milestone - your public perception, your fashion choices, the completeness of your collections, the monetary worth or lasting influence of your art, the popularity of your tastes - any way ambition can be measured - when you and everyone you love and everyone you disapprove of will be gone and forgotten in a hundred years or less?

How far can you take the rule of diminishing returns, before you have to find change? What if you haven't trained yourself to recognize it, and change passes you by?

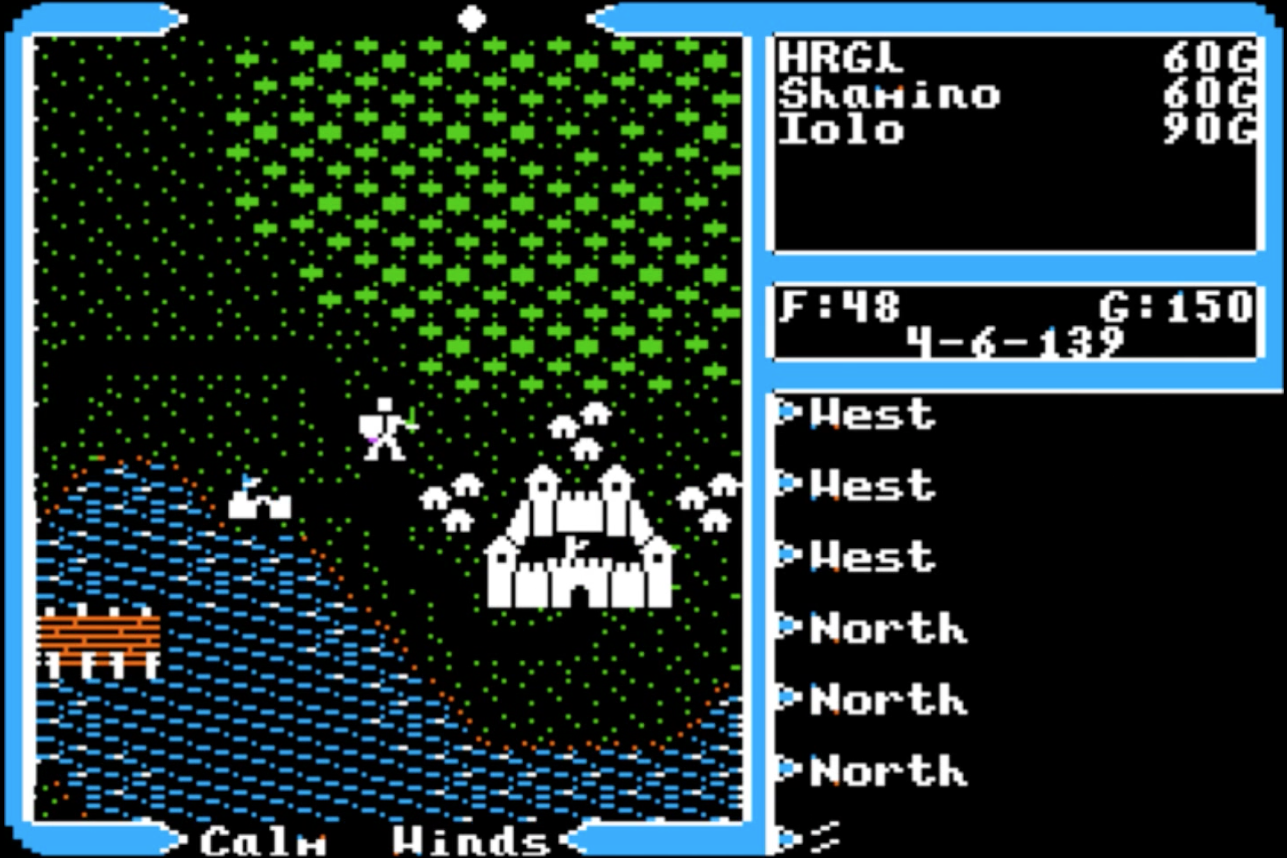

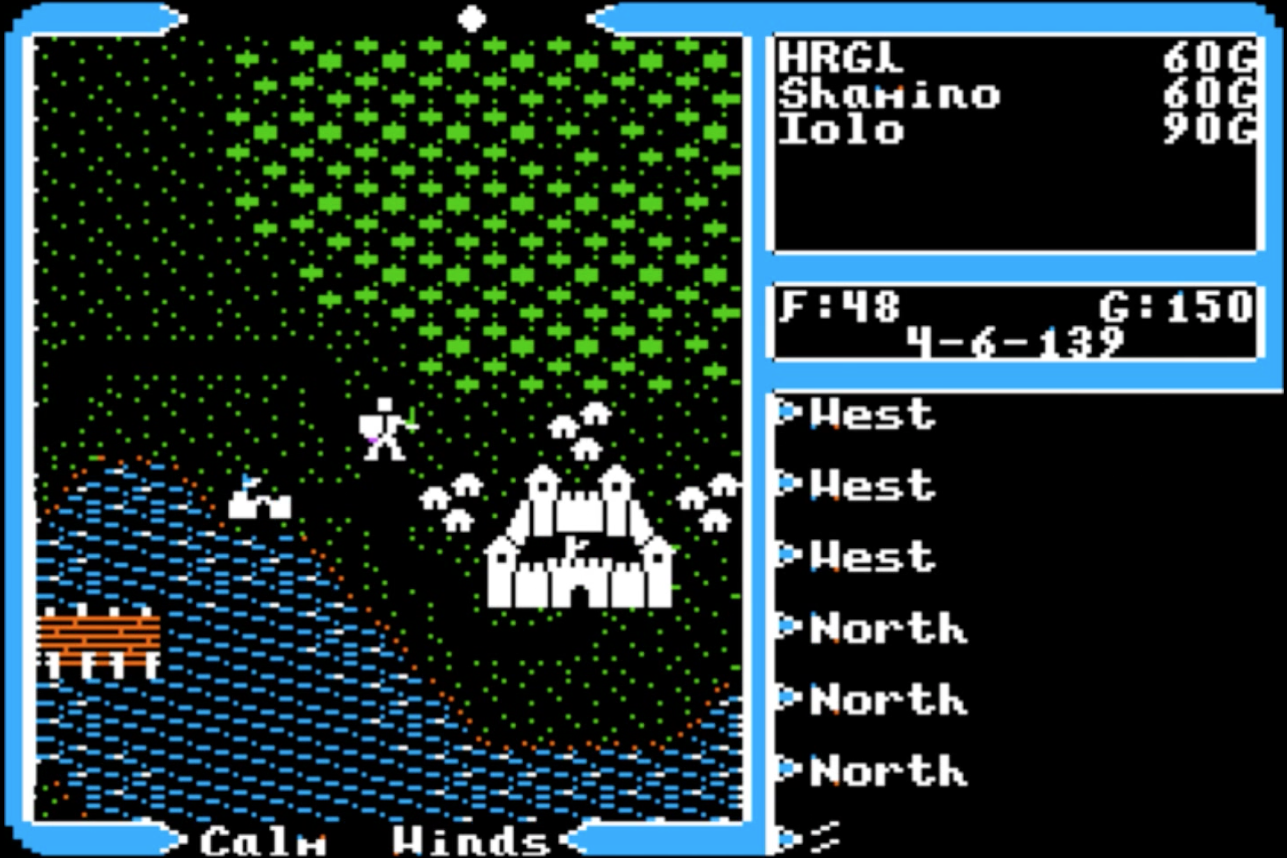

You have a sword in one hand, and a shield in the other. You are standing on a hilltop covered in grass. The grass is not green; it is jet black, and cut short like a carpet. This weird surface extends far before you into the distance over gently rolling hills until it meets an ocean. There is no seashore -- the grass simply plunges into the water, down beneath a roiling surface that has no orderly lines of breakers but is churning in all directions at once.

Out on this treacherous sea, in the distance, you can see bone-white monsters, with humped backs and long curving necks, looming up, and moving slowly towards you. Closer at hand you see restless humanoid creatures, pale-skinned and ghoulish, wandering slowly in your direction. They carry tridents and swords and clubs in their crude hands. They are silent, and unblinking, but they hit very hard. You will spend most of your time running from them, running between towns and their relative safety.

This is the landscape of Ultima II, as filtered through a child's imagination, based on the charming little graphics it lays out in tiles on the Apple II screen. It's easy to play, and pretty fun, but you have to spend a lot of your time restarting the machine because when you die, the game hangs, as though the whole universe has just stopped -- which is oddly appropriate.

This is the landscape of Ultima II, as filtered through a child's imagination, based on the charming little graphics it lays out in tiles on the Apple II screen. It's easy to play, and pretty fun, but you have to spend a lot of your time restarting the machine because when you die, the game hangs, as though the whole universe has just stopped -- which is oddly appropriate.

I played this game from start to finish, then busted out a disk editor and went exploring into the raw materials of the game. Lo and behold, all the maps that I'd been wandering across were there on the disk, in an uncompressed format, easy to modify. It only took a little bit of experimentation to put together my own editor.

The first thing I did was surround all the monsters by solid rock. Ha ha haaaa! Then I made bridges across all the oceans, and knocked holes through every mountain range. Phenomenal cosmic power! Then I went the other direction: Put a hundred demons on the map; channel them all into one valley. Kill them all in one absurdly epic battle. They don't leave corpses, but I could still imagine it - rolling black hills cut with a spiderweb of tiny channels, from the blood of a thousand clammy white eviscerated bodies. Awesome! Badass!

Then I built mazes, and prisons, museums. First on graph paper, then entering the data into the game with my editor. Why had the designers wasted so much space on big empty rooms, when they could have stuffed the map with twisty passages from end to end? My next-door neighbor and I decided that the modified maps were evidence of a vengeful god, or perhaps a sadistic dungeon master. We plugged the output from the Apple II into a video tape recorder, and plugged a microphone into the audio jack, and narrated the tale of a hapless adventurer wandering the planet while subject to the whims of an aggressively-voiced Arab wizard with the title "Nam Epod, Ruler Of The Sand". For those of you not juvenile enough to get the joke, that's Dope Man spelled backwards.

I actually have some of that recording transferred to a digital medium. For the sake of all mankind I am not putting it on the internet.

My family had a home computer, but they weren't loaded, so I got almost all my software through piracy. Taking what I could get, I skipped over Ultima I and Ultima III and pirated Ultima IV, then saved up my Christmas money and purchased Ultima V when it hit the stores in March of 1988.

Most people don't remember this, but there was a time when games came in a box, and with accessories inside the box. Not just some 'special edition' version of the game either, but every single copy, in the assertion that these items were a part of the experience, just as important as the bits and bytes on the disk. And I can tell you, they were. Ultima V came with a cloth map that you could hang on your wall, as though you had really traveled to a strange world where paper would not have been durable enough, as well as a shiny silver coin stamped with a mysterious design. In additional to the user manual was a separate booklet decorated to look like a few pages taken from a journal, and it was just as important as the map and the coin in setting the mood for the adventure to come. It told the tale of the great king Lord British, leading an expedition into a vast and terrifying underground realm called the Underworld that mysteriously opened up beneath his kingdom. He disappeared, and the expedition was lost. Now it's up to you to rescue the king and unravel the mystery!

Eventually you do enter the underworld, with your own band of heroes, and retrace the doomed expedition by following the landmarks described in the journal. It's a great example of interactive storytelling because it gives you the feeling like you're walking around in your own imagination, and the setting is dark and claustrophobic, and the game does not hold your hand along the way. If you run out of torches or magic, you will stumble around in darkness - until you run out of food, or are slaughtered. Horrifying monsters - described with plenty of detail in Lord British's journal - come slithering in from side caverns and up from underground seas, and close in behind your back. The torches only carve some of the darkness away, and you'll often catch a glimpse of an entire crowd of weird, hungry things, before they step back out of the light on the next turn. The Underworld is old-school hard, and it's also freaking enormous and doesn't come with a map, or an automap, so you are guaranteed to get lost. It's great!

I would play the game all day on the weekend, then wander around the Underworld in my dreams that night. I spent so much time there in my imagination that the memories of it are just as vivid as my memories of real places -- often more so. And of course, after I finished it I started poking around with a disk editor and changing things. Tweaking stats to make myself a god, altering the landscape, sowing confusion...

I would play the game all day on the weekend, then wander around the Underworld in my dreams that night. I spent so much time there in my imagination that the memories of it are just as vivid as my memories of real places -- often more so. And of course, after I finished it I started poking around with a disk editor and changing things. Tweaking stats to make myself a god, altering the landscape, sowing confusion...

One day I ran into a kid in my "junior lifeguards" class (a summer program where you spend a lot of time running up and down the beach) and told him about a program I'd written that converted every single mountain tile in the Underworld into cropland - a pretty clever hack that made the Underworld much easier to navigate, except that now all the critters everywhere around you could make a beeline through the crops and wale on you all at once. He laughed and said that was awesome, and asked for a copy of the program, which I brought to him a week later. At age 15 it was my very first contribution back to the "software community".

I bought and played the rest of the sequels later when I upgraded to a PC, and years after that I got inspired to write a parody of the Ultima series, called "Untima 9", which my friend Alex ported to the Mac. In retrospect the game is a nice time-capsule of all the things I thought were hilarious as an 18-year-old, though I do very seriously regret the way I parodied the "Take Back The Night" program I saw at UCSC. The sight of a huge throng of young women marching from one building to the next bearing lit torches was scary to me, and the negative reinforcement of "if this is scary for you, think about how we feel" was way too subtle for me to grasp. All I thought was, "Holy crap a mob with torches!! Where is this going?" (Whatever chauvinistic objections I might have voiced at the time have been handily silenced by making the modern Take Back The Night ceremony co-ed.)

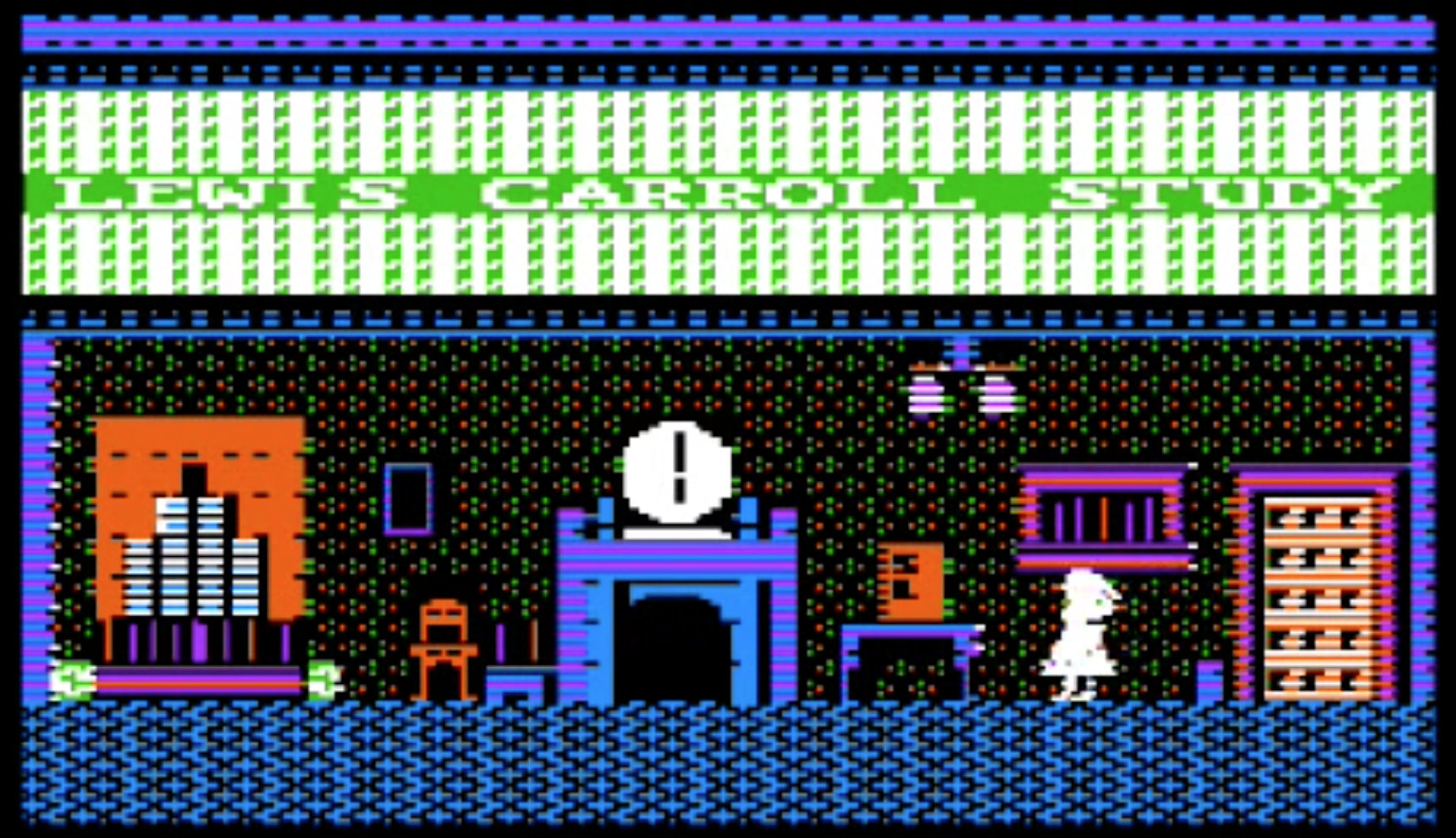

As a young kid with a hyperactive imagination, struggling to pin down the border between the external world and my own, I could relate to this game thoroughly. I often felt like I was on the edge of sanity, or that perhaps sanity was an illusion of an overly-compartmentalized mind, and if I explored the wrong compartments inside my own mind I could get lost and never find my way back to daily life and the real world.

I think this is one of the reasons young people are drawn to Lewis Carrol's work, and the idea of Wonderland. Their minds are still forming, and reality seems very plastic to them still. Little of the world makes sense to them yet, and it would be liberating if the world just dropped the pretense and stopped making any sense at all. We could forget about logic and learning and live by instinct alone.

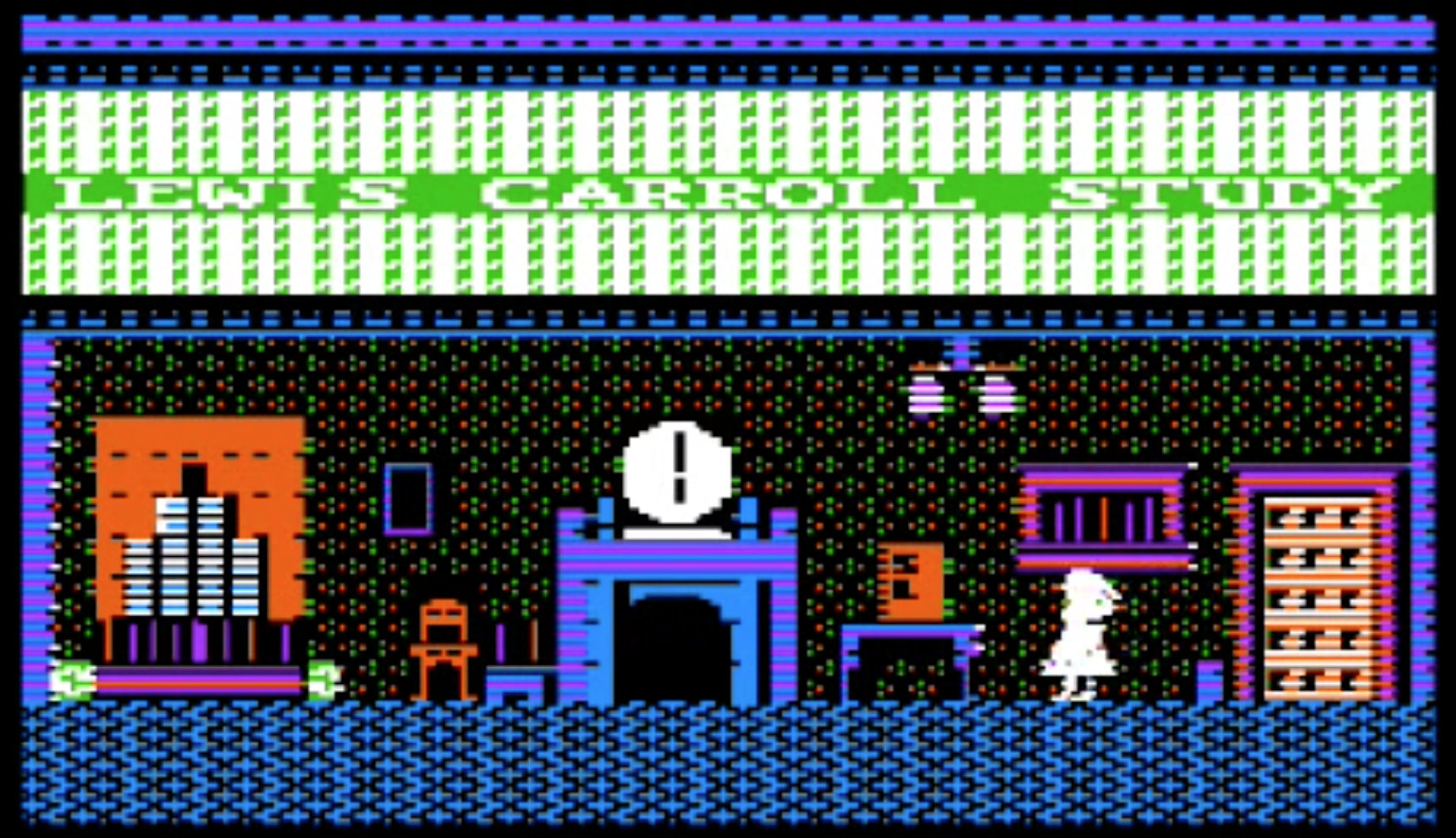

Anyway, this game - the Windham Classics version of Alice In Wonderland - is meant to be cute and whimsical, and it is. But by staying true to the source material it also brings along the same subtext. The game is open-ended, and playing the character of Alice, you mostly wander as you please through the twisted labyrinth of Wonderland, one screen at a time, using a hopelessly tangled network of doorways and passages - some of them one-way, some of them linked to multiple places - and have weird interactions with ghostly animated characters along the way. They're ghostly because they're rendered exclusively in black and white, in order to stand out against the colored backgrounds. The limited color palette of the Apple II also forced the designers to make the background for any exterior location - any landscape - jet black, accidentally giving the impression that all of Wonderland takes place underground, in tight passageways or in glowing structures standing silently at the bottom of a huge dark cavern. And since the premise of the story is that Alice has fallen asleep, and Wonderland is a dream, you - the player - are effectively playing a game where you wander through the dark, twisted contents of your mind, encountering ghosts who are all various degrees of insane, trying to escape before the whole thing disappears, taking you along with it. Totally wicked!

Anyway, this game - the Windham Classics version of Alice In Wonderland - is meant to be cute and whimsical, and it is. But by staying true to the source material it also brings along the same subtext. The game is open-ended, and playing the character of Alice, you mostly wander as you please through the twisted labyrinth of Wonderland, one screen at a time, using a hopelessly tangled network of doorways and passages - some of them one-way, some of them linked to multiple places - and have weird interactions with ghostly animated characters along the way. They're ghostly because they're rendered exclusively in black and white, in order to stand out against the colored backgrounds. The limited color palette of the Apple II also forced the designers to make the background for any exterior location - any landscape - jet black, accidentally giving the impression that all of Wonderland takes place underground, in tight passageways or in glowing structures standing silently at the bottom of a huge dark cavern. And since the premise of the story is that Alice has fallen asleep, and Wonderland is a dream, you - the player - are effectively playing a game where you wander through the dark, twisted contents of your mind, encountering ghosts who are all various degrees of insane, trying to escape before the whole thing disappears, taking you along with it. Totally wicked!

For me, this was ground zero for the kind of playing experience I mentioned in my description of Skyrim, and what I called the "Alice In Wonderland" effect.

The Apple II computer wasn't actually powerful enough to re-draw everything on its screen more than a few times a second. I know it sounds absurd in 2016, where we consider full-screen movies a basic human right, but those were the limitations back in 1985. So, the game designers had to create Wonderland as a series of static areas, mostly self-contained single screens. Then they threaded these areas together with doors. A hole in a hillside could be a door. A fireplace could be a door. A mirror could be a door. A window, a mouse hole, a gap inside a cloud, the rectangular spray underneath a fountain - these could all be (and were) doors. The result is a fragmented reality: You could create a map for Wonderland using squares and connecting lines, but there is absolutely no physical way that all the rooms fit together in the same physical space. It just doesn't add up.

The limitations of the Apple II hardware forced the design in other ways. Wonderland is big, but it's mostly unpopulated. You spend most of your time alone. The characters you do encounter are only able to do a few things, so they loop in on themselves, like ghosts fettered to the spot where they died, re-enacting their trauma. They usually vanish when you give them an item or say the right thing, as though you have laid their spirit to rest. Wonderland is also very static: Nothing ever decays. No matter how long you linger by the seashore, the ocean will be completely flat. A fire in a hearth will stay lit forever, and the room will always be exactly the same temperature, and the grass will never grow. You could wait in one place for eternity, or only a moment, and the experience would be the same. Everything is drawn in bold primary colors, using jagged textures of interleaved lines. It's like walking around inside a stained-glass window.

The limitations of the Apple II hardware forced the design in other ways. Wonderland is big, but it's mostly unpopulated. You spend most of your time alone. The characters you do encounter are only able to do a few things, so they loop in on themselves, like ghosts fettered to the spot where they died, re-enacting their trauma. They usually vanish when you give them an item or say the right thing, as though you have laid their spirit to rest. Wonderland is also very static: Nothing ever decays. No matter how long you linger by the seashore, the ocean will be completely flat. A fire in a hearth will stay lit forever, and the room will always be exactly the same temperature, and the grass will never grow. You could wait in one place for eternity, or only a moment, and the experience would be the same. Everything is drawn in bold primary colors, using jagged textures of interleaved lines. It's like walking around inside a stained-glass window.

It's a design that was just as much a product of the limited hardware and the state of the industry, as of purely artistic decisions. Those restrictions were not seen as desirable, by the authors or by me, but it didn't matter: It was what it was. The authors didn't intend to create a psychedelic haunted metaphor for madness, but I was an impressionable young person with my own vivid imagination, and enough of their design ended up that way for me to find it there. When the Nintendo came out I jumped on that, and on the Apple IIgs, and I jumped on every other hardware advancement I could afford, and very quickly the design limitations that spawned Alice In Wonderland were totally gone. Nevertheless, this game dropped an anchor into my subconscious mind, and even when I played Skyrim 25 years later I was returning to Wonderland, coming back to that same well.

When really good VR comes into its own, ten years from now, I will create a universe of rooms, rendered in tiny glowing blocks under a jet black sky, interconnected in bizarre ways, and it will feel like home.

The name Nethack isn't very accurate, especially nowadays. It creates a vision of hackers doing kung-fu in The Matrix. WHAA-CHAAAH!!! The 'hack' part of Nethack is actually short for hack'n'slash, like what you would do to a bunch of monsters with a sword, and the 'net' part just means that you can play it over a network, sitting in front of one computer while the internals of the game are percolating away on another one. It's not even multi-player. In fact, it's astoundingly crude-looking, and would probably not even qualify as a game to most people. At first glance it sure doesn't look like one; it looks more like what a typewriter would see if it had eyes and someone stuffed it inside a termite mound.

But in the 80's, it was legendary. And though it's not much to look at, it's deep and sophisticated, and wickedly old-school hard. You will die a hundred times before you even understand half of what's going on.

I wrote an epic, multi-part essay about my adventure finishing the game - or at least, beating it one time. It was the only way I could convince myself to stop playing it. The central idea of the essay is that Nethack is the ultimate game for stimulating the imagination. Nethack is also appealing to me on a personal level.

I grew up in a house surrounded by redwoods. The space between the trees was dark, quiet, and eerie. I used to go walking around there at night, and it was like entering an enormous cavern. If you've ever been camping in the redwoods you've had a taste of this. Get up and walk away from the campfire, well away from any other people, away from the voices, and shut off your lantern. You are instantly lost in a silent, vaulted space like a cathedral. The sky is erased by branches. The heaps of fallen redwood spines devour all sound. Now your imagination starts to fill in the vacuum. Wraiths come drifting silently around the tree trunks. Wolves and huge wildcats come padding towards you. Hungry demons, deranged undead things, reach long arms out to touch the back of your neck...

Yes, that's the deep woods. It creates an instinctive reaction. And it translates easily to the setting of Nethack, with its deep caverns and underground rooms, where you do not climb a mountain or drive through a city or cross a sunny landscape to get to the next level ... you go down. Down, into the dark, and down some more, and the creatures you meet get a bit more unnatural and vicious with every staircase, until eventually you're fighting eldritch monsters and confused beasts from different mythologies, and after that, the denizens of hell. With all kinds of one-off surprises on the way.

So it was, that the deep caverns of the redwoods I grew up in and the deep dungeons of Nethack got cross-wired in my imagination, and walking the terrain of one felt like walking in the other. Once in high school I got the bright idea to combine the two directly: I ran an extension cord and a very long phone cable out of the house and into a tent I set up on the edge of the forest, and connected an old WYSE-50 greenscreen terminal and a modem. Then I spent the whole evening and night in the tent, dialed in to a local BBS, playing Nethack inside my real-world Nethack of the redwoods. It was an act totally unique to Santa-Cruz-area 1980's computer geek and fantasy nerd culture, and it's long gone now, but it's so throughly planted in my psyche that it might as well be in my genes.

Some distance down, the dungeons of Nethack branch off into the Mines of Moria and you can go tooling around in there. I had quite a thrill when Peter Jackson showed us that place on a movie screen years later -- it was like seeing old vacation photos. I wanted to prod the fellow next to me and say "I've been there!!"

Anyway, I blather on for pages and pages about Nethack in the essay I mentioned, so if you're geeky enough to want more, check it out.

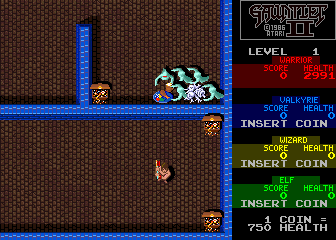

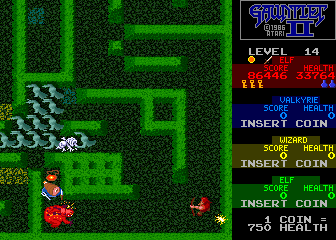

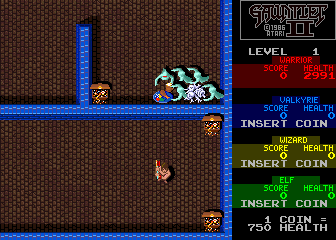

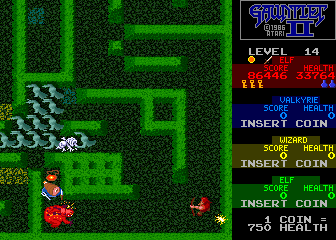

This silly little arcade game is threaded deep into my subconscious mind. After almost 30 years I still have dreams about it.

You choose one of four characters. Then you get a top-down view of a twisty maze, and your character appears in the maze with a puff of smoke and is immediately beset by monsters. At the same time, a timer appears on the right side of the screen, and counts slowly down to zero. When it hits zero, you die. The only way to delay your death is to go charging through the maze and find helpful items. If you have friends standing around, they can choose a character and grab a joystick, and they get plopped down into the maze right alongside you.

The game has a mean streak. When your timer drops below 200, a snide voice announces your imminent death. "Green elf ... is about to die!" it says, or "Blue warrior ... your life force is running out!" or perhaps most famously, "Wizard needs food ... badly!" That one became a catchphrase for a while and is still drifting around in pop culture.

If you manage to stave off death and finish the maze, you get about four seconds to catch your breath. Then you're dropped instantly into another maze just as twisty as the last one. More traps, more doors, more dead ends, and more monsters, crammed in shoulder-to-shoulder, itching to beat you down. That's Gauntlet II. Round after round of twisty mazes, with no end, until you die.

Also, you're punished for having a high score: The more treasure you pick up, the faster the monsters get, so if you fight through the mazes without taking any loot you can see a whole lot more of the game. Just like many things in life, there's a way you can play to maximize your score, and a way you can play to maximize your fun. The difference is even more obvious with two or more players on the board. You'll trip over each other, fight over food, shoot each other by accident (or maybe on purpose)... You're guaranteed to die faster with friends. But you're guaranteed to have a blast before you do.

I played this game for hours and hours as a teenager, usually alone, in the tiny beleaguered arcade that opened for a while in my home town. The sounds and visuals are a part of me, but even deeper than those, the feeling of fighting through an endless maze is carved into my mind like the necropolis under a cathedral.

Life is an endless series of rounds. Some go your way, some don't. Either way the rounds continue, and the only thing you can count on - no matter what - is that eventually you will die in the maze. In the meantime, you have choices to make that will shape the next round. Those choices are your treasure. They are everything.

1. (Age 16) Super Merryo Trolls

Less than ten people on Earth have ever played this game -- because it was a little project that I took on with two of my friends in high school, and we never finished it.

Yes, we were geeky enough that we thought it would be fun to code up a computer game together. And it was! We had a shared base of source code. We wrote special tools to manage art and music, and build levels. We had endless discussions, wrote each other documentation, made checklists, delegated tasks. We tried to cram every deranged juvenile idea we could into the design.

This was a time before code repositories and version control, before "open source" had a community, before computing devices came with a software development kit full of tutorials and searchable help and frameworks. Our "shared base of source code" was really a heap of files that we passed around on floppy disks. Our design documents were scribbles in graph-paper notebooks. Yet somehow, the effort found a kind of discipline, and we got pretty far along before graduation and college split us apart.

In the beginning, the code I wrote was a mess of repetitions and non-sequitur variable names. My idea of helpful commentary was stuff like "This part sucks" and "this is the bit I was talking about yesterday". Sometimes I would paste in jokes and ASCII art. My friends complained bitterly when they had to work on it, and slowly I got better. The improvement boosted my confidence. When the ideas I had actually worked out, I got my first taste of that highly addictive feeling of being an innovator -- that feeling people spend their lives chasing in the software industry. The idea that I could have fun with friends solving puzzles, and be productive at the same time, set me up for a programming career. Having fun with it -- that was the key!

The game was an excellent conversation starter at job interviews, and probably helped land me my first real programming job. Much later, a dozen years after we stopped working on it, I wrote a long essay about the experience, and that essay gave a serious boost to my career. I went in for a job interview and the people across the table had already heard of me through the essay! (I have my friend to thank for that actually - he passed the link around before I applied for the job.)

Super Merryo Trolls was never finished, but the experience of building it puts it right at the top of this list. It's hard to imagine a game being any more influential. It means as much to me as those childhood pick-up basketball games mean to a top member of the NBA. It made me.

Honorable Mentions:

Civilization

Many words have been spilled about this game's legendary ability to compel players to take "just one more turn." I've spilled many myself, and instead of spilling more, I will point you to the essays I wrote, each more elaborate than the last: 1995, 1998, 2011.

Many words have been spilled about this game's legendary ability to compel players to take "just one more turn." I've spilled many myself, and instead of spilling more, I will point you to the essays I wrote, each more elaborate than the last: 1995, 1998, 2011.

That first essay in 1995 was the start of a trend in my writing, where I'd play a very immersive computer game and then retell the experience in story form, with all the anthropomorphizing I'd done in my head along the way weaved in. It was a way for me to live the experience twice, and make a framework for pinning down the random thoughts I had about game design or philosophy - and of course the dumb jokes - along the way. Since then, of course, the internet has exploded with written and video-based play-alongs done by millions of people. I can't say I'm a trend setter because I don't think anyone of consequence ever read the things I made...

I also need to honorably mention the fifth game in this series, Civilization V, but for a different reason: It hooked me just as surely at the first game did, in a different era of my life, and infected me with a desire to travel across the world and see the ancient places name-dropped in the game. And that took further shape as a wild-eyed series of bicycle trips. A fair chunk of my middle-age time has been spent on a bike -- "behind bars" as we tourists sometimes call it. How much of that was Civilization goosing my interest in anthropology? I'll never know.

Robot Odyssey

It's circuit design as a game. Yep. How the heck could that ever be fun?

Well, you do it underground in the dark with obsessive-compulsive creatures. That makes it more relatable perhaps?

This game was extremely challenging. And I don't mean in terms of coordination or memorization - it wasn't about hitting buttons at just the right time, or repeating an action until you won by brute force - it was challenging in a legitimate engineering sense.

This game was marketed to 15-year-olds with the cute bloopy robots, but if you finished this game unaided, you were essentially performing electronic circuit design at an upper-division college level or beyond. The puzzles within would stump the majority of the adult population on the planet. And not because of cultural or language barriers either. Most adults simply would not be able to bend their minds around in the way required to solve these puzzles.

Robot Odyssey was like that arcade machine in the movie "The Last Starfighter": If you could beat this game, it was proof you had bona-fide real-life talent for engineering and could be useful in the industry almost immediately. I truly feel like the kids who finished it should have been subject to an aggressive recruiting push from Silicon Valley companies.

As a kid, I was also really taken with the idea that the things in the sewers of Robot Odyssey were intelligent creatures - up to a point - but they were also wired to automatically react in certain ways, just like the wiring of instinct in living things. If I put my hand in hot water, I instinctively recoil, and yet I'm still a thinking being who can process the event. So how much of life is being a robot? You do what you are wired to, and react the way you're wired to react, and your only option in life is to accept this and find some route to happiness or understanding.

Might and Magic / The Bard's Tale

These games take the fundamental weirdness of Dungeons And Dragons mythology and put it front and center, primarily through the colorful, playful artwork.

These games take the fundamental weirdness of Dungeons And Dragons mythology and put it front and center, primarily through the colorful, playful artwork.

They made a perfect fit for computing: What better thing to convey, through a mathematical simulation on a flat, cold computer screen, indoors in a shadowy room, than an imaginary world where big hairy sweaty people were romping around in the sunshine, wearing exotic clothing, swinging giant clubs and sharpened hunks of metal, and beating on each other and screaming and shedding blood? It's about as far from the physical act of using a computer you can get. That's no coincidence.

I definitely can't say this applies to everyone, but I know for sure it applies to a significant chunk of the young computing population around me as I was growing up: We gravitated to sword-and-sorcery games on the computer because we liked the idea of being outdoors, with friends, with no bigger responsibilities than to physically bludgeon some certified evil antagonist until they either fled or died, and then sit around a campfire congratulating each other and making jokes, before doing the exact same thing again the next day. Of course, we couldn't really do that. The closest we got was camping trips, parties, and organized team sports, with the occasional schoolyard fight thrown in.

So we fed those urges indirectly, by doing something totally unrelated that we also liked: Sitting indoors quietly, going on internal mental journeys with the aid of the interactive digital fiction on the computer.

The more you think about it, the more - and less - sense it makes...

Chronotrigger

This game is a great realization of choose-your-own adventure storytelling. It's an open world -- sort of. The decisions you make are often mixed in with straightforward plotting, in a way that blends the two. Chronotrigger has won many awards over the years for its elegance.

But, this game has stuck with me for over 25 years mostly because of one incident that opened my eyes to the power of choice in game design.

Chronotrigger is a game about time travel. Early on you gain the ability to move between different eras of human development, like an anthropologist having the best dream ever, and later you gain access to a time machine that gives the characters finer control over where and when they go.

There is a character named Lucca. She's styled as a "nerdy scientist inventor" type, and she's instrumental to the plot of the game. There is a tragedy in her past: Her mother lost the use of her legs when Lucca was a child.

In the middle of the game, seemingly at random, all the protagonists are gathered around a campfire in a forest and the topic of Lucca's mother comes up. Everyone agrees it's tragic, and then they bed down for the night. The screen goes dark, and players naturally assume that the next thing they see will be the campground in the morning.

Instead the screen fades back in to the campground at night, with everyone asleep except for Lucca. She's up, and standing there. There is no music. With nothing happening, the player is compelled to poke a few controller buttons, and discovers that Lucca is now the character being played. The situation is clear: Lucca has unfinished business, and before she can sleep, there's something she must do.

After poking around, the player discovers that Lucca can walk away from the campsite and into the forest, where a time portal appears. She passes through it and the player is taken to a scene inside Lucca's childhood home.

The player guides the adult Lucca out onto an upstairs floor, with a view down to the workshop below. As we watch, a tiny child version of Lucca appears, helping her father with a machine. An accident happens, and the machine falls on top of Lucca's mother. The child begins running around, screaming, not knowing what to do. The machine needs to be shut off, but no one can get to the console.

Tragic music underscores the events that unfold. It is unclear what the player needs to do here. It's possible to explore the upstairs area a little and find a console that needs a password, and if the player guesses the password - Lucca's mother's name, Lara - then the machine is shut off and her mother is saved. But it is also possible - even likely - that the player will fail to figure this out in time, and the adult Lucca will be plunged back into the present moment in the forest, with no ability to go back a second time.

That's what happened to me. I didn't guess the password, and after a while of watching young Lucca run around screaming for her tragically injured mother, I was ejected into the present. All I could guide Lucca to do at that point was go back to the campground and bed down with the rest of the party. She'd revisited a terrible, formative moment from her own past, watched the tragedy all over again, and changed nothing.

I went on from that scene and continued the game, eventually finishing it, but the negative outcome stuck with me. Clearly something powerful had just occurred. Years later I learned that there had been academic papers written about that one scene, because the way it was designed was novel in gaming. It was an example of a new kind of narrative involvement in a tragedy, or perhaps just a really intense spin on a very ancient form of audience participation.

The player nominally has control over the character, and is responsible for the decisions and the effort the character makes, yet circumstances occur - maybe by design, maybe by choice - that make the character fail in their mission, and from that point on the character and the player are both forced to bear the burden of that failure together. The player has not just failed to find a happy ending, the player has personally failed a character they care about.

What made this incident special, aside from how novel it was in video games at the time, was how smartly it was handled. In the dialogue of the game, it's clear that Lucca is attempting to go back and correct a tragedy that she feels responsible for, and that was also formative in her personality. If - or when - the player guides her to fail in this effort, Lucca discusses it further with her friends the next morning, though she doesn't admit that she actually went back and tried to prevent it. The game actually shows Lucca trying to do the emotional processing that's needed to accept the failure, and again, since the player has been complicit in the failure, the player comes along for the ride.

Since that scene in Chronotrigger there have been endless examples of failure built in to video games, including failure with no possibility of positive outcomes, and many of these examples are reviled by players, who feel they are being railroaded into making poor choices or doing despicable things just for the sake of being hurt or even punished by the game designers. "The Last Of Us" is probably the biggest example of this in recent gaming. My own distaste for the way "The Last Of Us Part 1" ended was so great that I steered clear of "Part 2" entirely. It's bad enough that the main character selfishly invalidates everything you've accomplished over the course of the game. What makes it reprehensible, is that you are personally forced to move the controller and steer the character through that bad choice, even as you loathe it. Though you previously had control over whether they entered a room or fired their weapon, the game mechanics narrow down around you. There are many rooms but you can only steer into one. You have many possessions but the only one you can access is a weapon. And so on.

The worst examples of this tactic omit the emotional processing before and afterward. Like a tamagotchi showing a rotting digital corpse and declaring "YOU FAILED", with no comfort or guidance: What was the point? Why play a "game" if it makes you feel railroaded and sad afterwards?

In Law Of The West, I played the new sheriff of a small frontier town, having a series of conversations with various townsfolk. Each citizen walked out into the middle of the screen with a herky-jerky animation, then turned to face me and started talking. I got three or four responses to choose from, and the dialogue branched out. This went on for a while until the citizen walked away, or until they drew a weapon - or I drew mine with the joystick - and somebody got gunned down. Over the course of a game I could have conversations with the town drunk, the local doctor, a tough-talking cowboy, a schoolteacher, a kid, and some others. Depending on how I steered the conversation, I got a chance to stop a robbery, drive a troublemaker out of down, or even go on a date.

In Law Of The West, I played the new sheriff of a small frontier town, having a series of conversations with various townsfolk. Each citizen walked out into the middle of the screen with a herky-jerky animation, then turned to face me and started talking. I got three or four responses to choose from, and the dialogue branched out. This went on for a while until the citizen walked away, or until they drew a weapon - or I drew mine with the joystick - and somebody got gunned down. Over the course of a game I could have conversations with the town drunk, the local doctor, a tough-talking cowboy, a schoolteacher, a kid, and some others. Depending on how I steered the conversation, I got a chance to stop a robbery, drive a troublemaker out of down, or even go on a date.

Every situation I get into is a chance for me to pursue something, and usually the thing I choose to pursue will be the thing I find. If I don't make that choice consciously - if I don't diversify my pursuits and learn to find more than one kind of thing - my world will close in around my pursuits like a thickening forest, and my ability to find happiness will close in at the same time.

Every situation I get into is a chance for me to pursue something, and usually the thing I choose to pursue will be the thing I find. If I don't make that choice consciously - if I don't diversify my pursuits and learn to find more than one kind of thing - my world will close in around my pursuits like a thickening forest, and my ability to find happiness will close in at the same time. This is the landscape of Ultima II, as filtered through a child's imagination, based on the charming little graphics it lays out in tiles on the Apple II screen. It's easy to play, and pretty fun, but you have to spend a lot of your time restarting the machine because when you die, the game hangs, as though the whole universe has just stopped -- which is oddly appropriate.

This is the landscape of Ultima II, as filtered through a child's imagination, based on the charming little graphics it lays out in tiles on the Apple II screen. It's easy to play, and pretty fun, but you have to spend a lot of your time restarting the machine because when you die, the game hangs, as though the whole universe has just stopped -- which is oddly appropriate. I would play the game all day on the weekend, then wander around the Underworld in my dreams that night. I spent so much time there in my imagination that the memories of it are just as vivid as my memories of real places -- often more so. And of course, after I finished it I started poking around with a disk editor and changing things. Tweaking stats to make myself a god, altering the landscape, sowing confusion...

I would play the game all day on the weekend, then wander around the Underworld in my dreams that night. I spent so much time there in my imagination that the memories of it are just as vivid as my memories of real places -- often more so. And of course, after I finished it I started poking around with a disk editor and changing things. Tweaking stats to make myself a god, altering the landscape, sowing confusion... Anyway, this game - the Windham Classics version of Alice In Wonderland - is meant to be cute and whimsical, and it is. But by staying true to the source material it also brings along the same subtext. The game is open-ended, and playing the character of Alice, you mostly

Anyway, this game - the Windham Classics version of Alice In Wonderland - is meant to be cute and whimsical, and it is. But by staying true to the source material it also brings along the same subtext. The game is open-ended, and playing the character of Alice, you mostly  The limitations of the Apple II hardware forced the design in other ways. Wonderland is big, but it's mostly unpopulated. You spend most of your time alone. The characters you do encounter are only able to do a few things, so they loop in on themselves, like ghosts fettered to the spot where they died, re-enacting their trauma. They usually vanish when you give them an item or say the right thing, as though you have laid their spirit to rest. Wonderland is also very static: Nothing ever decays. No matter how long you linger by the seashore, the ocean will be completely flat. A fire in a hearth will stay lit forever, and the room will always be exactly the same temperature, and the grass will never grow. You could wait in one place for eternity, or only a moment, and the experience would be the same. Everything is drawn in

The limitations of the Apple II hardware forced the design in other ways. Wonderland is big, but it's mostly unpopulated. You spend most of your time alone. The characters you do encounter are only able to do a few things, so they loop in on themselves, like ghosts fettered to the spot where they died, re-enacting their trauma. They usually vanish when you give them an item or say the right thing, as though you have laid their spirit to rest. Wonderland is also very static: Nothing ever decays. No matter how long you linger by the seashore, the ocean will be completely flat. A fire in a hearth will stay lit forever, and the room will always be exactly the same temperature, and the grass will never grow. You could wait in one place for eternity, or only a moment, and the experience would be the same. Everything is drawn in

Many words have been spilled about this game's legendary ability to compel players to take "just one more turn." I've spilled many myself, and instead of spilling more, I will point you to the essays I wrote, each more elaborate than the last:

Many words have been spilled about this game's legendary ability to compel players to take "just one more turn." I've spilled many myself, and instead of spilling more, I will point you to the essays I wrote, each more elaborate than the last:  These games take the fundamental weirdness of Dungeons And Dragons mythology and put it front and center, primarily through the colorful, playful artwork.

These games take the fundamental weirdness of Dungeons And Dragons mythology and put it front and center, primarily through the colorful, playful artwork.